Go and Do Likewise

In Which I Read The Parable Of The Good Samaritan

It struck me sometime in the middle of the night that the Bible Stories that prove most confusing to our age are the ones that have to do with love. And unfortunately, because God is love, and the Bible is the vehicle through which he tells us about himself and his love, most of it is thus rendered incomprehensible. And this is a sad thing, for love is such a basic and necessary experience. Without it, no one would be able to function, let alone flourish.

I was sort of surprised, over the last week, scrolling around the internet, to hear so many ghastly takes about the Good Samaritan. The strange exegetical gymnastics that cause some to say that Jesus is a racist bad guy in his interaction with the Syrophoenician woman, or that letting Mary sit at the feet of Jesus to be taught instead of forcing her to help Martha in the kitchen somehow reinforces the patriarchy, or any of the ideological nincompoopery that’s been dished up over the last ten years, should melt away under the light of the Good Samaritan story. And yet, of course it doesn’t. Because love is at the heart of the story, as well as pity, or, in modern parlance, empathy. And so here is JD Greer trying to make the story about reparations. And here is Duke Kwon. And here is a climate change option. And here is a bonfire of vanity.

The reader who doesn’t pause to reflect upon hearing the punchline, that one should “go and do likewise” will blithely say, “Sure thing.” As though having neighbors and loving them is nothing impossible. And yet, the magnitude of what Jesus is holding out to the lawyer who asks the question is as great as that offered to the Rich Young Ruler who also wanted to know what he had to do to attain eternal life and went away sad when he discovered it meant loving God more than his own comforts. Here, the lawyer discovers something just as shocking—what kind of love Jesus has for us.

And behold, a lawyer stood up to put him to the test, saying, “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” He said to him, “What is written in the Law? How do you read it?” And he answered, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” And he said to him, “You have answered correctly; do this, and you will live.”

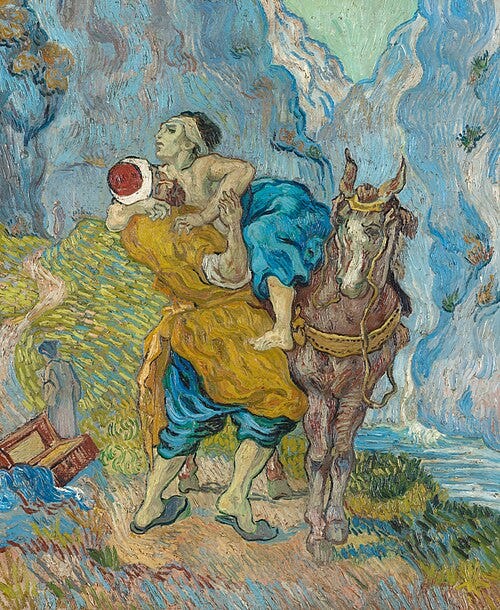

But he, desiring to justify himself, said to Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” Jesus replied, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers, who stripped him and beat him and departed, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road, and when he saw him he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he journeyed, came to where he was, and when he saw him, he had compassion. He went to him and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he set him on his own animal and brought him to an inn and took care of him. And the next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper, saying, ‘Take care of him, and whatever more you spend, I will repay you when I come back.’ Which of these three, do you think, proved to be a neighbor to the man who fell among the robbers?” He said, “The one who showed him mercy.” And Jesus said to him, “You go, and do likewise.”

The first thing to observe, of course, is that if the Lord Christ has said something to you, and your first desire it to “justify yourself,” you might want to stop scrolling and reflect. The problem, though, is that we all want to justify ourselves rather than being justified by the blood of Jesus. We want to be good and to receive the just reward for our goodness. And if we are discovered not to be good, that’s ok, we can lie and say we are. Also, it’s ok for me to say “we” here because we all are inclined the same way.

Second, and follow me closely here, the theological beating heart of this story isn’t justice. It isn’t getting something that you deserve or don’t deserve. It’s about the man who comes along and takes pity. It’s about mercy.

Mercy is such a difficult concept for the modern online person, who is caught in a powerful web of continual self-justification. We are quick, in our content consumption, to judge one thing from another. And we have been taught to believe that our works of justice have the power to change the world.

Third, we, who are not like the Good Samaritan, who, in the story, is Jesus, are supposed to try to be like him. And this is impossible, for we are all the other characters in the tale. For example, the man who went along the treacherous road from Jerusalem to Jericho could reasonably be scolded for not knowing better. What did he expect from a journey notorious for gangs of robbers? He should have gone in the company of another person, or not at all. But he didn’t. He went alone, and the thing everyone knew would happen did happen.

And then there are the robbers themselves. If you want to allegorize—which is a fine thing to do—you might wonder to yourself who you have unwittingly whacked, spiritually of course, not physically, and left wounded by the side of the relational highway. I spent part of the week asking God if I have gotten into any really bad habits that have disappointed other people. Relationships come and go, and I hate it when they go. When has it been my fault that this has happened? When have I trucked along like the lawyer, unable to see the spiritual carnage of hubris, anger, or apathy? Don’t worry. I didn’t dwell on this question too long. That would have been uncomfortable.

And then there are the two men, the Priest and the Levite, who, like so many, gave a wide, virtue-signaling, self-righteous berth to suffering. They were busy letting their ordered lives confess the beauty of Christ’s peace—one of my favorite lines from a favorite hymn—or at least, that’s what I would have told myself if I had walked by and needed to make myself feel better. These two men have good boundaries. They have jobs that prohibit them from coming into contact with death, which the man by the side of the road looked to be. If they couldn’t do their jobs, how would they feed their families? And if they couldn’t feed their families, they would starve and be thrown out into the street, like the man there. So, really, walking around is the loving thing, the responsible thing, the necessary thing.

Except that the man by the side of the road wasn’t dead. He was alive but gravely wounded. He had no power in himself to help himself. There was no health in him. He was in a pit partially dug by himself and then thrown into by others. If no one helped him, he would surely die.

So, after a while, a stranger came along who possessed the means, the will, and the ability to stop, anoint the wounded man, put him on his donkey, take him somewhere comfortable, and pay for all his needs. And when you see that that is the call, then, of course, you would want most particularly to know who is your neighbor and will want it to be a very small number of people, if any. Worse, the only way to discover who is your neighbor it is to feel, in the depths of your being, compassion for someone beside yourself.

And that is almost impossible, for our world is exhausted by false compassion, or, as some like to call it, untethered or toxic empathy. I am meant to feel for myself, first and foremost. If I don’t love myself, I can’t possibly love you. And so the kingdom of the actual neighbor has been traded for the unseen, potential neighbor who may or may not exist. It is socially acceptable to unceasingly bear the weight of guilt over the intangible but vaguely righteous question of reparations or climate change, and to ignore that the first neighbors who deserve your pity are those who are close by you, within physical proximity to you who may not agree with your politics, or not even know what they are.

Who might those people be? For me, they are my actual neighbors with whom I have no real relationships, something I feel sad and guilty about, but helpless to amend. Fortunately, these are not my only neighbors, for there are a lot of people in my church, and in my home, and the old lady at the self-checkout who gets angry about having to weigh her vegetables, and the people at Planet Fitness, and the network of relationships that has slowly grown over twenty years.

There are a lot of overlooked neighbors in our world. Many women, if they are counting things up, might consider having pity on their unborn children, instead of being all the other characters in the story. People in the government might try thinking of the citizens of their country as their neighbors, rather than people from whom to extract money. CEOs of tech companies could wonder to themselves who are their neighbors, and try not to enslave and impoverish all people everywhere.

In each case, though, there is certainly an actual person close at hand who is suffering who needs not to be ignored. With the help of the Lord, who helps you, you might find yourself helping other people without even knowing it. You will be moved with pity and you will give your little all and no one online will notice. And you will do it because of the love of Jesus, and not because you are good, or justified, or righteous. Jesus left his throne and came into a strange country and found you and picked you up and healed you. And when you are healed by him and loved by him, through the Holy Spirit, you will often find yourself helping others.

And that’s as it should be. And now, so that you can find some neighbors, go to church. Hope to see you there!

Ouch.

You indict me here--I count myself in several of the groups you point out. And it is so helpful to be reminded that I can't save myself, which is the exact opposite message I keep hearing from the "culture." Brilliant, incisive, moving. As usual, Anne. God bless you.